Four Dead Horses Read online

Page 3

He felt sorry for his mom. Why hadn’t he been kinder to her? Why hadn’t he listened, or reacted at all, during her weekly calls, shown a little enthusiasm for the shake-up in the cotillion decoration committee or concern for the progression of Gra Gra Newport’s gout. Granted, their communications had followed a set pattern that didn’t allow Martin much more of a return than “that’s great” and “neat” to Dottie’s volley of bullets on the Fuzzy Balls. But Martin hadn’t even tried. He’d been so caught up in his newfound life of the mind. And now she was dying, and for all his reading in the constructive and cultural studies of religion (two quarters, Eastern and Western), he could find no meaning in her impending demise, just regret. And a little resentment. Maybe. After all, she could have made even the teensiest effort to understand him, appreciate, even celebrate, his accomplishments, which were not insignificant. But it was always Frank she fawned over, his backhand down the line, the wave in his golden hair, his popularity with the PPHS cheerleading and lifeguarding set. Who cared that Frank read at a sixth-grade level? Who cared that he dented her Oldsmobile on a beer run to that place in Baroda that doesn’t card?

Carroll and Frank returned to the table, and Frank returned to narrating the disputed tennis match. Martin interrupted.

“How long does she have?”

“She’s not going to die, you moron,” said Frank.

Martin looked at his dad.

“She doesn’t have to die,” Carroll said, as if this were his wife’s choice, like deciding whether to get Ho Hos or Chips Ahoy at the Hilltop Grocery. “Betty Ford didn’t die.”

“Right,” said Frank, “but tell him about the operation.”

Carroll drained his glass. Dottie was scheduled for a full mastectomy the last week of May. She’d be in the hospital at least ten days, depending on how it went, then home with another few weeks of bed rest. The timing of this, which depended on the schedule of “the best breast man money can buy,” was terrible. Frank was due at Dick Gould’s Junior Summer Tennis Camp in Palo Alto the weekend before the operation.

“And I gotta go to this.” Carroll pushed a flyer toward Martin. “For Rotary. In Kansas City.”

Martin looked at the single, mimeographed sheet. “Isn’t the ERA dead?”

“Still in the courts. This is an emergency meeting. A club in California let in women, two women,” said Carroll.

“And you’re putting together a posse to ride from Kansas City to oust them?” said Martin.

Carroll poked at the flyer. “I’m a keynote speaker, look at that. I’m representing all of the upper Midwest.”

“At least all the males,” said Martin.

“Don’t kid yourself, smartass. There are a lot of women who don’t think they should be in Rotary either.”

Martin sympathized. He’d attended a Rotary meeting five years ago in the company of the PPHS assistant principal, Mr. Jimkowski, as a reward for a high PSAT score. They were served partially rehydrated mashed potatoes, canned peas, and breaded perch for lunch; a speaker from Plasti-Fab Inc., a four-man tool and dye shop specializing in safety and warehouse signage, droned for forty-five minutes on the dangers—economic and environmental—of recycling; and the meeting closed with a song about the benefits—economic, environmental, and spiritual—of manhood. Those who didn’t join in the chorus with enough verve had to throw a quarter into the tin can provided by the Pierre Rotary Committee for Crippled Children.

“I’m speaking on the day Dottie goes to the hospital. And she can’t drive herself,” said Carroll.

“That’s exam week,” said Martin. “Let Frank be late to summer camp.”

“Are you listening?” said Frank. “He said Dick Gould’s Junior Summer Tennis Camp. Twelve weeks. Invitation only. Dick Gould’s Junior Summer Tennis Camp, as in Dick Gould, as in McEnroe’s coach. McEnroe, as in John McEnroe, as in the best player of all time.”

“It’s what your mom wants,” Carroll said. “She knows you’re good at school. You can make up your work.”

“I am good at school. But final exams,” Martin said, with less resistance. Had his family discussed this, decided that he was the one best suited to take on the awesome responsibility of caring for his mom on her deathbed? That he was the one smart enough and compassionate enough and strong enough? Had someone, his dad even, sat at the dinner table, the same table where Martin had endured countless, endless, incoherent tales of Frank’s tennis victories and his dad’s business conquests, and said, “Martin’s the man for the job.”? His face warmed, and he blotted his forehead with a scrap of tissue from a metal napkin dispenser.

Frank muttered into his empty plastic mug. His cheeks blinked orange in the neon light of the malfunctioning Schlitz sign over the bar. He lifted his head and said, “You know, I’m having to miss my exams, too.”

Of course. Nothing new here. Martin swiveled to see if he could snag a witness. He expected Frank to point out next that there was “no I in ‘team.” The bartender held up a stubby finger.

“Set ’em up,” Carroll said, and Frank giggled like a tipsy schoolboy, which, Martin supposed, was the case.

“What about Mrs. Newport, couldn’t she take care of Mom for a few days?”

“Well, here’s the thing,” Carroll said, “Dottie doesn’t want anyone to know. We’re telling people she’s going in for surgery, but on her elbow. Tennis elbow.”

“So you see,” Frank said, “Mrs. Newport can’t take her to the hospital, because she’ll see that mom is going into the breast wing and not the elbow wing.”

“Tennis elbow,” said Martin. “Jesus.” He stood up. “I won’t do it.”

“Think about it,” said Carroll. “I need you. Frank needs you.”

“And Mom,” mumbled Frank and looked into his lap. His face hollowed out, became the face of the five-year-old their dad had shoved shivering out to the end of the high dive. Martin liked Frank back then.

“We can talk about it more in Arizona,” Carroll said. “But it’s not like you’ve been pulling your weight in the family lately.”

“Your considerable weight,” said Frank and snickered.

Martin dug in his pocket to find some money. He wanted to throw it down, say something dismissive, like, “This is for the coffee, see you in hell.” His shorts were a little tight, though, and it took a while to pry out what he thought was a dollar bill but turned out to be a receipt from the Korean wash-and-fold. His dad and Frank had already returned to talking tennis anyway. Martin exited, distressed and relieved that neither called out to him to wait.

Martin took the seat across from his mom and ran his finger through the milky coffee blob left by the Weber acolyte. The mug, half full—or Martin supposed, in this circumstance, half empty—sat in front of her. Her palms pressed flat on the table.

“How was the tour?” she said, head down. “I need a manicure.”

“We didn’t do a tour,” said Martin. “Dad and Frank are at Sammy’s getting drunk.”

Dottie nodded, as if she he had known that. “I suppose I should join them.” She didn’t move.

“They told me about the operation.”

“Oh,” she said. “It’s nothing. Tennis elbow. I don’t even think they put you out for it. I tell you what needs a serious operation. These cuticles, that’s what.”

She looked up at him with empty eyes.

“They told me it was cancer,” Martin said. “Breast cancer.”

“Tennis elbow,” she said.

Martin put his hands on top of hers. Her bones shifted under thin skin. She pulled her hands into her lap.

“When Bitsy had her operation on her tennis elbow, she was back on the courts in no time,” she said.

And then she started to cry.

April 7, 1985

Dear: Oliphant Family, Cabin #14

Yee-haw! Welcome to Jimmy Sneedle’s Te

nnis and Dude Ranch. We hope you are settling in fine, and if you have any questions or concerns, please contact Mary Anne in housekeeping (x-4359), Tricia at the front desk (x-4350), or Bibby Jean in the dining room (x-4952). If all else fails, head over to the Sunshine-on-my-Shoulder Saloon in the main lodge. As bartender Tommy Tonic says, “Ain’t no squeaky wheel a Long Island Iced Tea can’t grease.”

Dinner tonight is at 7:00 pm in the Chow Wagon Dining Room, and we’ll be offering our traditional Sunday supper of Oysters Rockefeller, Celery Rémoulade, Beet Salad with Dijon Crème Fraîche, and brandied pears for dessert! The cocktail special of the day is Sex on the Beach!!

At 8:30, we’ll hold an orientation session around the grand fireplace, and you can get more information on all the fun activities we’ve got planned this week. Sign up there for midnight poker (adults only), a tasting of 1980 Bordeaux led by Jimso himself (with an opportunity to bid on a case from Jimso’s personal cellar), the round robin tennis challenge (junior, ladies, and adult brackets), Marketing Director Mark Buffington’s slide presentation on upcoming real estate opportunities at the ranch, child care (full day and overnight options available), and so much more. We’ll also give you the out-west-low-down on Jimso’s Jamboree and Talent Show, our end-of-the-week entertainment extravaganza.

After orientation, the bar will be open until 2 a.m. with rhumba dancing to the Latin beat of the ever-popular Jimmy Sneedle house band—Músicos con Queso!!

For those interested in horseback riding, barn manager Beaufort Giles will offer a mandatory safety briefing at 9:00 pm in the billiards room.

Welcome again to a week of WILD WEST FUN, so hold onto your ten-gallon hats and make sure the cat gut’s tight on your racquet, because HERE WE GO!!

Happy Trails!

J

imso and the entire Jimmy Sneedle’s Tennis and Dude Ranch Staff

2

Martin spent the first half of his spring break week at Jimmy Sneedle’s Tennis and Dude Ranch in Wickenberg, Arizona, trying to get Carroll or Dottie to explain the extent of her deterioration and Martin’s role in her recovery. But should the C of cancer even form in his frontal lobe, his mom would dart away to take a fly-fishing lesson, and his dad would lasso the nearest employee to discuss the capitalization challenges of a dude ranch. Dottie seemed healthier than she had in March, perhaps rallying in the presence of the Newport family and the rest of the Fuzzy Balls royal court. But the operation was still on. Martin had received a Xerox of her hospital appointment reminder in the mail a couple of weeks ago. In the top left-hand corner of the sheet, Carroll’s secretary, Janet Priebe, had typed: “FYI, from your father. Bless you.” Mrs. Priebe was long serving, loyal, and didn’t range anywhere near the borders of Fuzzy Balls society. Martin supposed she would keep his mom’s secret.

He attempted again Wednesday at lunch. Dottie and Frank had left early to sit for a mother-son caricature by the ranch’s cowboy cartoonist. And again, Carroll cut Martin short, waving over Jimmy Sneedle himself, “Jimso” to paying guests. It took little prodding for him to hold forth on his purchase of the thousand-acre ranch from the Giles family, who had run it as a cattle operation for over a century.

“I got big plans, Mac,” Jimso said, waving a pudgy hand at Carroll, who didn’t challenge the nickname. He often complained that his given name ran counter to the essential virility of his character, and he never protested when he was assigned a more masculine moniker, no matter how random.

Jimso flapped his paw toward the dining room’s picture window. Palo verde trees and saguaro cacti glinted in the noon sun. He described a Robert Trent Jones golf course covering the riding trails; a Michael Graves-inspired clubhouse taking the place of the eighty-five-year-old barn; low-fat cooking classes instead of square dancing, California wine tastings instead of end-of-week gymkhanas. He would get rid of the horses and their sky-high liability insurance premiums. And he would fire barn manager Beaufort Giles, who “never goes a goddamn day without shooting me the stink eye.” Jimso and Carroll then fluted off into a martini-fueled duet on the ingratitude of underlings. Martin headed for the barn to read Shakespeare.

It was there that cowboy poetry first found him: April 10, 1985, not six weeks before the First Annual Elko Cowboy Poetry Confluence in Elko, Nevada. Martin lay on a pile of rough blankets, his head on a saddle, his feet propped on a pile of Western Life magazines and thumbed a ratty paperback copy of Hamlet. Sequestered behind a wall of hay bales stacked two high, he read to the clump of horse hoof on old wood and the mumbles of the ranch hands.

Hamlet’s grousing and Gertrude’s nagging drifted past him, like the sweet tang of horse manure floating in the barn’s stratosphere. He didn’t know why he was bothering. His professors for Macroeconomics II and Ancient Law had refused to let him reschedule final exams. Only the Shakespeare scholar on loan from Cornell was willing to accept a paper in lieu of the last test. He’d probably have to repeat the entire trimester.

He focused on the page, but Claudius’s elucidation on the nature of grief tangled with another soliloquy beaming in from somewhere beyond the hay bales.

I’ll tell you, boys, in those days

Old-timers stood a show,

our pockets full of money,

not a sorrow did we know.

So simple, the metaphor and rhyme. Martin’s cohorts in his English literature discussion group would have gone after the doggerel like picadors to the bull, poking it full of holes with exquisite irony and obscure references to Chaucer. As would have Martin had he been back in Hyde Park. But in this barn, the lines, more than any of Hamlet’s self-indulgent bellyaching, struck in him a minor chord to which he had not previously resonated.

It had to be in the delivery. Martin peeked past the hay to confirm the baritone twang was Beaufort Giles’s, a lean man with crackling brown skin, as if he had been cured next to the tobacco in the Marlboro always affixed to his bottom lip.

But, how times have changed since then,

we’re poorly clothed and fed,

our wagons are all broken down

and horses most all dead.

Beaufort stood, right leg a little forward of the left, knees soft, right hand extended and cupped, as if cradling an invisible Yorick cranium. Three wranglers faced Beaufort, backs to Martin, their leather-clad legs a row of null sets.

Soon we’ll leave this country,

then you’ll hear the angels shout:

“Oh, here they come to Heaven,

their campfire has gone out.”

Beaufort shut his hand and gave it a little shake. The wranglers broke out in loping applause. One whistled through his fingers and two horses whinnied in reply.

“That’s really good,” Martin said, before he remembered he was terrified of Beaufort, whom he had seen coldcock a foaming mustang two days earlier. “Did you write it?”

“Christ no, son,” said Beaufort. “That’s Ben Arnold. He died in ’22. He was one of the greats.”

“Greats?” said Martin.

“Great cowboy poets,” said Beaufort.

“What’s a cowboy poet?” Martin asked, unaware he had just posed the question the answer to which would give the rest of his life purpose.

Beaufort dug a boot toe into the barn’s dirt floor, spun a silver spur with a rust-brown finger, and hacked a nicotine-scented chortle. “Showin’s better than teachin’. Why don’t you practice with us, for the show?”

Martin had heard all about Jimso’s Jamboree and Talent Show from his mom, who was working up something with Bitsy involving kazoos. Beaufort explained that the performance always concluded with a cowboy poetry recital by the barn staff and any guests who might want to join. If Martin started practicing now, he could earn himself a solo spot.

Martin pursed his lips, a prelude to demurring, but before he could, one of the wranglers, the one with a handlebar mustache that drooped the l

ength of his neck, said, “Get that in a knife fight?” He flicked a rough hand at a small scar on Martin’s top lip, where he had sliced it on a chipped espresso cup.

“Sure,” Martin answered and found he meant both the scar and the poetry practice.

Over the next three days, between leading trail rides, Beaufort schooled Martin on cowboy poetry. Classics like Henry Herbert Knibbs’s “Where the Ponies Come to Drink,” and modern works like Bob Barnhardt’s ode to bull busting, “Born to Buck.”

Often, Beaufort’s daughter Ginger would stop by to listen. She was seventeen, a champion roper who threw her saddle on her silver cutter with the authority, fluidity, and grace of the kind of man Martin hoped to be someday. Yet she was not a man. Martin was aware of that.

She’d put her hands on her narrow hips, cock her head, drawl a backhanded comment like, “Not bad for an Eastern fella,” or “You won’t learn that at your university.” She’d wink or smile, and Martin would choke or blush. Beaufort would have to snap his fingers and jangle his spurs to get Martin to focus again.

On the afternoon before the Saturday show, Martin and the hands ran through their performance for the last time before Beaufort and the others left to lead the sunset rides. Martin remained in the tack room, eyes closed, whispering the words to “The Campfire Has Gone Out” to himself and running his fingers along the swirls tooled in the leather fender of the saddle on the stand before him.

“Do you study stagecraft in Chicago?” said Ginger.

“Jesus,” Martin squeaked and coughed to lower his voice back down to his practiced baritone. “I didn’t see you. Where did you come from?”

“Born here on the ranch, like my daddy and his daddy before. And you?”

“Michigan,” he said.

“The big lake they call ‘Gitchee Gumee’?”

“No, I think that’s Superior. We’re near Lake Michigan, you know, the one that steams like a young man’s dreams. Gordon Lightfoot’s great.”

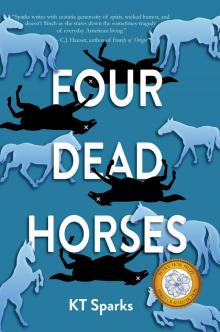

Four Dead Horses

Four Dead Horses