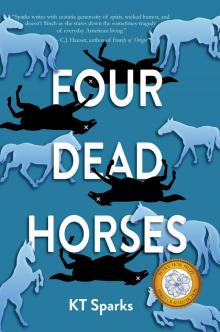

Four Dead Horses Read online

Page 2

Martin looked at the roan horse, now trying to snap at the razor-sharp beach grass along the bottom of the dune, drawing its black lips back to reveal teeth like cracked hunks of yellow quartz. It didn’t look wild. It looked hungry. And a little bored.

“It fell, and she wrenched her leg dismounting. She just avoided being crushed. Crushed! You can see in its eyes, it’s evil,” said Dottie.

The roan sighed into a prolonged fart, then stretched its neck back and pointed its snout to the sky, as if it expected oats to rain down like manna from horse heaven.

“What about Julie?” said Martin. “Looks like her horse is pretty crazy too.” He gestured toward the water, and the roan startled, pivoted, and trotted back toward Bitsy.

“That’s Bitsy’s horse in the water,” Dottie sobbed. “That’s the beast that threw her. And Julie won’t stop fussing with it. Bitsy might have broken something. Come, please, Martin.” Dottie wrapped both hands around his arm and tugged at him. Martin felt a thump at his chest, as if he’d swallowed a slug of Diet Rite too quickly. His mom needed him. Bitsy Newport needed him. Perhaps there was a chance to exit Pierre on a note of, if not heroism, then at least competency.

He followed Dottie down to the shoreline, watching Julie all the while. She was a powerful swimmer. Already, in her sophomore year at PPHS, she’d shattered the girls’ record for the 100-yard butterfly. She was on her knees at the horse’s thrashing head. Waves regularly doused her, and once the horse’s muzzle caught her in the jaw, she went under.

When Martin and Dottie reached Bitsy, she looked up and said, “I’m fine, but aren’t you nice? Maybe just a stick to lean on?”

“You are so brave.” Dottie looked as though she were about to fall to her knees and bawl, a cripple at the feet of a bemused Jesus Christ. Instead, she slung her shoulders back and said, “I will get that stick. Martin, find your dad and tell him to bring the Lincoln as close as he can.” Dottie turned and ran to a driftwood pile, dove toward a branch, then tilted further forward, windmilling both arms. Her feet flew back, kicking up silver slivers of shad.

“That is exactly how my horse fell,” said Bitsy, in the quiet tone of someone talking to herself about the weather.

Martin jogged after his mom, who jumped to her feet. Her legs, from the pink border of her footies to the edge of her Fila tennis skirt, were covered in sand and fish guts. Her Lacoste polo had ripped at the front, and blood seeped through the fabric under her right breast.

“Mom, you’re hurt,” he said.

She ignored him, bent down, and grabbed a piece of driftwood from the ground, carefully wiping the fish scales from it.

“I’ve got to get back to Bitsy. Go get your dad. Go,” she said.

Dottie scuttled sideways, right arm pressed to her side, left fist raised, brandishing the walking stick, Lady Liberty with her tricolor. Martin considered staying with her until it was clear how bad her injuries were. But she wouldn’t want that, or anything that might interfere with her opportunity to be of service to Bitsy Newport.

Julie yelled from the water, “Goddamn it, Martin, help me. This horse is drowning.”

Martin looked to see if his mom had noticed. She should be pleased. Julie Newport knew his name. And sought his counsel. Unfortunately, he wasn’t much of a swimmer. Given his size, people expected buoyancy of him, but he had never floated. Even at the YWCA beginner’s class, where every minnow was allowed to cling to a kickboard, he would still sink. He remembered there had been a kind of peace there underwater, listening to the gargled bellows of the instructor, Mrs. Thurk. Peace, but not aquatic competence. He thought of relaying that history to Julie, but held back, sensing the time was not right. Anyway, it didn’t look like more than a couple of feet deep, when the waves weren’t crashing over the horse and the girl. And he did truly want to be the sort of man who would bound to the rescue in this sort of situation, without overthinking exactly what this sort of situation was. He made his ways through the alewives and into the lake. He hadn’t worn the right shoes.

“Hurry! I can’t hold his head anymore.”

The horse rolled onto its back and churned its legs, one hoof dangling at an odd angle from the fetlock. Its massive jaw gaped, and its nose spewed green foam. An eye spun around, then fixed on Martin, and the upended animal froze. Martin used the moment to strategize his approach.

Before his plan gelled though, the horse groaned and smashed onto its side, its back hooves kicking into the space into which Martin had been about to step. Damn it all, he needed a hero’s playbook here. Who was he supposed to save? Julie? The horse? Himself? Went with himself. He bicycled back to dry land.

“Don’t go,” Julie sobbed. “We’ve got to keep his head up.”

“Don’t be ridiculous,” said Bitsy, walking to where Martin stood. Dottie hobbled behind, still clutching the driftwood branch. “They’ll have to shoot the nasty thing anyway. Martin, I believe your mother is injured. Perhaps time to go for your father?”

“Buster, his name is Buster,” screamed Julie, hugging the horse’s stilling head. “Martin, please. He’s dying.”

He so wanted to dive in, prop the horse with one arm and Julie with the other, take in the yelps of surprise and admiration from his mom and Bitsy Newport. And Julie. But not this time. Not yet. Martin turned and trudged up the dune toward Twin Bluffs’ offices.

When Martin returned with his father and two Dozzis, Buster’s corpse was beached. A bedraggled and weeping Julie sat legs splayed in the alewives, cradling the horse’s head.

“I’m afraid we’ve had a little accident here,” said Bitsy, as if she were the queen apologizing for her corgi lifting a leg on a potted plant. Dottie, propped on the driftwood stick, croaked, “Bitsy needs to see a doctor.”

Carroll’s eyes swept over the tableau, and he smiled at the quaking Dozzis. “Don’t suppose you’ve got liability coverage,” he said.

Bitsy Newport sustained only a minor sprain and was able to host her annual Kentucky Derby party that afternoon, a sprig of mint tucked rakishly in the folds of the Ace bandage around her left ankle. Dottie Oliphant watched 21-1 long shot, Gato del Sol, win the 108th Run for the Roses from her bed at Swinehurst Hospital. The gash at her sternum took eleven stitches to close, and she broke a rib on her right side.

There were two fatalities on the beach that day: Buster, of course, and the Dozzis’ dreams for their resort. By the next Friday, Carroll Oliphant had purchased Twin Bluffs at a bargain basement price, agreeing to assume legal responsibility for the riding accident. He bet that the aggressively genteel Newports wouldn’t think of suing over something as trivial as a sprained ankle, and he was right.

By August, Carroll had stripped the place of every rental Sailfish and nautical-themed decorative item and sold it all to a couple starting an inn on Florida’s Longboat Key. The only asset he couldn’t monetize was the bubble. No one seemed to know how to take the thing down. So he gave it to his wife, who spun it into social gold. Soon she was hosting the Fuzzy Balls’ Mixed Doubles tourneys, carpooling with Bitsy and her husband to the Swiss Shack on Thursday evenings, and partnering with Bitsy in the bubble’s regular Tuesday morning ladies league. For a brief time, Dottie soared, riding the social updraft she had always known she was meant to catch. Even after her crash, Martin in equal part envied and took comfort in the fact that she, at least for a couple years, had been able to inhabit her own version of the American dream.

Frank won his semifinal match 6-2, 6-0, 6-1.

The Second Horse: Chopo

d.1986

Seventy-Sixth Annual Conventional of Rotary International

Emergency Plenary Session

“WOMEN IN ROTARY IN THE ERA OF E.R.A.”

May 28, 1985

Kansas City Convention Center

Kansas City, MO

All ROTARIANS are invited to an EMERGENCY PLENEARY SESSION to

take place during the SEVENTY-SIXTH ANNUAL CONVENTION OF ROTARY INTERNATIONAL to discuss a UNIFIED and INTERNATIONAL response to the continued attempts of women to infiltrate the ranks of SOME (former) ROTARY CLUBS and the impending decision of the SUPREME COURT OF THE UNITED STATES on the validity of ROTARY INTERNATIONAL’s expulsion of the Rotary Club of Duarte, California for the admittance of THREE females in 1976.

10:00 a.m. Welcome and Benediction

The Very Reverend Bill Beaverton, Chevrolet Mission Baptist Church of the Redeemer in Faith,

Rotary Club of Milledgeville, Tennessee

11:30 a.m. “Stop in the Name of Love: What to Do When the Ladies Come a-Callin’:

Handling Applications from Women: A Discussion”

Mitch Ragsdale, Rotary Club of Fort Worth, Texas

12:30 p.m. Luncheon and Keynote: “No Girls Allowed: Keeping the Gals Out of the Clubhouse, for Their Own Good,

and Ours, and the Nation’s”

Carroll Oliphant, Rotary Club of Pierre, Michigan

1.

1985 was a fine time to be at the University of Chicago. On any given day, Saul Bellow and Alan Bloom might be discussing Kierkegaardian relativism in front of twenty-year-olds who read their first chapter books the year Bellow won the Nobel Prize, while Eugene Fama, still a quarter-decade from his Nobel, drew supply and demand curves for an Econ 101 class. Muddy Waters regularly headlined at Buddy Guy’s Checkerboard Lounge, ten blocks north of campus; Jimmy Cliff and Run DMC appeared at Mandell Hall; and the Lascivious Costume Ball, an annual mélange of porn flicks, professional strippers, Ancient Greek erotic poetry, and naked nerds, raged at Ida Noyes.

From the day of his matriculation, Martin took to U of C like bacteria to an agar plate. He read Plato’s Republic until three a.m., played Space Invaders in the basement of the Woodward Court dorms with his laundry quarters, and cheered on the hapless varsity Maroons as they took to storied Stagg Field to be decimated by various junior colleges.

C—H! Chicago!

C—H! Chicago!

What is C—H for?

Methane!

He spent summers at the front desk of the Regenstein Library, shivering in the overextended air conditioning, getting a jump on his reading for the next quarter, and making the pocket money that would keep him in Eduardo’s stuffed pizzas and Morry’s subs the rest of the year. Summer before his junior year, he moved to one of the student slums on Blackstone Avenue with two roommates he rarely saw. Like him, they used the apartment for sleeping and changing underwear and the library or the classroom for the rest of life. He was alone much of the time, but no more alone than the majority of his classmates, who drowned themselves in books the way most college students of that decade drowned themselves in grain alcohol mixed with Hawaiian Punch and cocaine.

So it was not unusual that he stood alone outside his apartment that day in March of 1985. He picked at the hem of his Levi’s cut-offs and watched his dad help his mom out of a Checker Taxi and halfway into a curbside snowbank. He’d last seen his family two months ago at Christmas break. They’d all be together again in less than a month for spring break with a coterie of Fuzzy Balls families at Jimmy Sneedle’s Tennis and Dude Ranch in Arizona. The unprecedented level of togetherness made his stomach buzz with unease.

Dottie waggled a slush-sheathed red pump, and Carroll took her arm, then both arms as her clean foot shot under the idling taxi. Frank came around the back, cracking his neck. Martin walked down the path from his apartment building to the sidewalk.

“Hey, welcome to Chicago. Sorry about that.”

“Never mind,” she said, pulling her mink tight around her. “Where are your pants, Martin? It’s freezing.”

Martin was sure his mom had lost weight. Even under her fur coat, which puffed with static like a cattle-prodded cat, she looked like Nancy Reagan, a starving and tense starling. That was the style, he supposed.

“Show us some leg,” Frank cackled, and Martin wished he’d worn the full-length jeans he had initially pulled out of his closet. But the temperature reached fifty-two this morning, and that meant spring at U of C. Shorts, Frisbees, and legs as white as the scrap paper upon which students noodled through the millionth or so decimal place of Pi.

“We should probably get going,” Dottie said, took one step forward, then sank to her knees on the sidewalk, talking the entire time. “Or maybe a quick sit, to get one’s breath, just a moment, or a glass of water, that might be the thing.”

Carroll tugged at her arm with one hand, while the other brushed dirt from her coat, “She’s all right. Just overheated. A thousand dollars’ worth of fur, she better be overheated.”

“Mom?” Martin said and walked to her, went in for a hug. Damn, she was thin.

“I’m fine. Just tired.” She started to sag down again. Carroll put an arm tight around her waist and bounced her once. Her mouth gaped open and snapped shut, but she stayed upright.

“I think I’ll probably just sit out the tour,” she said.

A college tour for Frank was the ostensible reason they had gathered today. Martin had his doubts. Frank was an average student with an above average backhand, and, last Martin had heard, was interested only in Stanford. Certainly not the U of C, whose teams did participate in the NCAA, but in division III, and with a great sense of irony.

“There’s a café on 55th,” Martin said.

Martin looked back from the exit of the Café Medici to where they had left his mom. She sat across a rough and scarred table from a frizzy redheaded boy in a poncho translating Die protestantische Ethik und der Geist des Kapitalismus. She held a mug of chamomile tea in front of her mouth but did not drink. Instead, she stared at the laboring student, as if he were a gorilla inventing the wheel and she were Jane Goodall, catching it all from behind a mufungu tree. Martin followed his dad and Frank out.

“Let’s get a drink,” said Carroll.

“Great idea,” said Frank.

Martin considered pointing out that it was only eleven in the morning. Martin considered pointing out that it had been five years since Illinois had raised the drinking age to twenty-one and, in any case, Frank was only seventeen. Martin considered pointing out that even the most basic tour of the U of C campus, one that skipped the interior of Frank Lloyd Wright’s Robie House and the Oriental Institute’s special exhibit on the excavations of Persepolis, would still take at least two hours. But he did not. To do so would have been to assume his father could get through more than an hour of interaction with his family without a drink, preferably stiff. To do so was to assume a college tour for Frank had ever been anything but a fiction. To do so would have been to delay finding out what really rocketed his family out of their well-loved world and into Martin’s, a distant moon in which they had shown little interest in the past.

They walked in silence down 55th Street to Woodlawn Avenue and pushed inside Sammy’s Tap. Smoke hung low, though none of the daytime regulars were smoking. Martin inhaled and shut his eyes, savored the smell of ancient cigars, stale beer, and yesterday’s sauerkraut. Frank hacked and put a hand over his nose.

Carroll turned to the bar. He elbowed between an old woman in a plastic rain hat and a burly man in a black White Sox T-shirt. “Martini, dry, rocks, twist, and…” Carroll raised an eyebrow at Martin and Frank.

“Coffee, black,” said Martin.

“Miller, Genuine Draft,” said Frank.

The bartender cocked his head, shrugged, and turned away. Martin trailed Frank and Carroll to a Formica table on the opposite wall. As soon as Frank sat, he launched into a monologue about some tennis match during which he felt he had been cheated or treated with less than adequate respect. Carroll clasped both hands in front of him and stared at Frank, nodded, grunted. It was like watching “Meet the Press.” Except dumber. And Martin couldn’t change the channel.

“We’re not three blocks from where Enrico Fermi

first split the atom,” said Martin, which silenced the other two until the bartender slouched over with their drinks.

As Carroll lifted his glass, he said, “So, you see how it is with your mother? How she was back there?”

“What’s wrong with her?” Martin took a sip of coffee. It seared down to his gut. His mom hardly ever got sick. Everybody in Pierre went around for half the winter with chapped lips, feverish eyes, and crumpled tissues poking out of the pockets of their parkas, but never his mom. She didn’t even buy Kleenex. The rest of the family had to spend the flu season blowing their scabbing noses on toilet paper.

“She’s got cancer,” said Carroll, poking the lemon peel into what was left of his drink.

“What?” Martin pushed back in his chair. The legs screeched against the floor like skewered peafowl.

“Cancer of the…women’s parts,” Carroll answered.

“Ovarian cancer?” Martin squeaked. A girl in his European Literary Realism class sophomore year had ovarian cancer and didn’t even make it to the end of the section on Balzac.

“Breast,” said Carroll.

Martin shook his head. Bile crept up his esophagus, bypassed his mouth, headed for his eyes.

“I’ll get us another round.” Carroll returned to the bar, and Frank followed, empty mug dangling from his hand. They both talked for a while to the bartender. Carroll slung an arm over the shoulder of the old woman. Frank hooted something at the Sox fan.

Martin thought, perhaps, they were giving him a moment to take in this terrible news. He tried to envision his mother laid out in a casket, white, lined in burgundy silk, he in a new suit taking the hands of the mourners. Looking into the eyes of their neighbors, the Burrows and that older son who never recovered from Vietnam. Accepting an awkward hug from Bitsy Newport, who would be in black Dior.

Four Dead Horses

Four Dead Horses